Total vaginal hysterectomy (TVH) is the preferred route of hysterectomy. Consider the following facts:

- TVH is an average of $3,500 cheaper per case than total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and about $5,000 cheaper per case than robotic hysterectomy (RH).

- TVH is associated with not only less cost, but shorter recovery time and fewer complications, including lower risk of urinary tract injury, bowel injury, thromboembolism, and mortality.

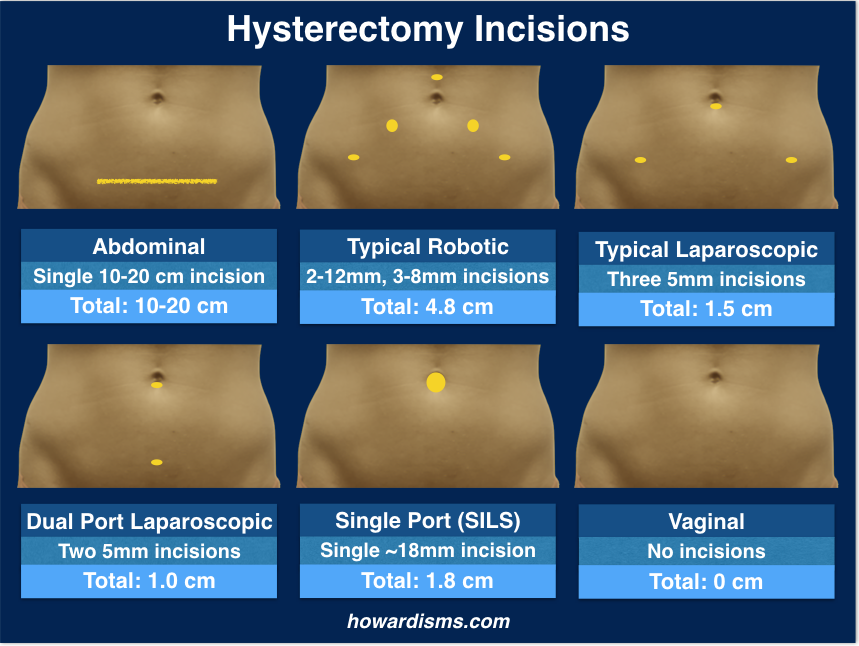

- TVH is the least invasive approach, with no abdominal incisions (and none of the potential risks associated with them) and better cosmetic results. It is the original natural orifice surgery.

- Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists recommend TVH as the preferred method of hysterectomy.

Despite these clear and undisputed facts, vaginal hysterectomy appears to be on the decline. Dr. Thomas Julian has written a wonderful and prescient commentary (in 2008) about this paradox, entitled Vaginal Hysterectomy: An Apparent Exception to Evidence-Based Decision Making. He discusses some of the reasons for its decline, include clever marketing, the myth that “newer” equals “better,” and, mostly, a lack of training for current residents and post-graduates, who more and more feel uncomfortable performing what I (and I suspect Dr. Julian) consider to be the easiest method of hysterectomy. Consider these facts:

- Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed each year in the US.

- In 2005, prior to the advent of robotic hysterectomy:

- 22% of cases were vaginal;

- 14% of cases were laparoscopic;

- 64% of cases were abdominal.

- The robot was supposed to be the panacea to end abdominal cases. In 2012, the landscape had changed:

- 14% of cases were vaginal;

- 16% of cases were laparoscopic;

- 39% of cases were abdominal;

- 31% of cases were robotic.

- So vaginal cases were reduced by 36% and abdominal cases by 39% due to the robot.

- Studies have consistently shown that between 70-85% of all cases could be performed vaginally in average hands, with experts reaching rates above 95%. For full disclosure, I have averaged 96.5% vaginal hysterectomy over the last eight years in a panel of patients that has a considerable amount of endometriosis and uterine fibroids, using laparoscopic assistance in about 10% of cases (and usually realizing it was unnecessary at the end of the case).

So when will the decline in vaginal hysterectomy end? What can be done to reverse the trend? Why don’t doctors believe in evidence-based medicine? All of these are excellent questions. I suspect that the trend will not reverse itself until payers start insisting that less expensive hysterectomies be done whenever possible. I believe that teaching residents (and post-graduates) a simplified approach to vaginal hysterectomy, so that they are more comfortable with the procedure, can aid in increased utilization. And, yes, doctors do not believe in evidence-based medicine; even many of those who claim to actually do not. C’est la vie.

Here is my simplified approach to TVH:

- Placement of short, weighted speculum and Deaver anterior retractor.

- Give IV indigo carmine, if available, with the bladder drained (no catheter).

- Grasp the cervix with a single and a double toothed tenaculum (increasing amount of traction that can be performed without tearing tissue).

- Infiltrate the tissues around the cervix with a vasopressin (10 U)/bupivicaine 0.25% solution.

- Make a deep circumferential incision 3-4 mm above line of reflection of the anterior vaginal wall from cervix (visible when pushing the cervix cephalad).

- Identify the vesicouterine space (by elevating the vaginal tissue and dissecting vertical bands of connection tissue) and place a Deaver retractor in this space in order to elevate and protect the bladder.

- Make a posterior colpotomy sharply with Mayo scissors.

- Tag the posterior peritoneum with a suture, then place long weighted speculum through the posterior colpotomy (place a small sponge to protect the bowel if not much uterine descent).

- Ligate the uterosacral ligaments with a Glennard clamp or Heaney clamp (usually in one bite but perhaps in two if not much descent).

- Make anterior colpotomy if easily accessible. If not proceed with next step.

- Ligate the cardinal ligaments/uterines with Ligasure.

- If anterior colpotomy not previously made, try again.

- Continue up the broad ligament with the Ligasure on both sides.

- Invert the uterus if possible, delivering the fundus into the vagina through the posterior colpotomy.

- Ligate the upper pedicles (round ligament, fallopian tube, and ovarian vessels) with the Ligasure.

- If unable to deliver fundus, then take upper pedicles in the normal vaginal manner but pack the bowel back with a wet sponge.

- If uterus is too big, morcellate it.

- After removal of the uterus, remove packing and inspect for hemostasis.

- Run and lock posterior cuff; place culdoplasty sutures and suspension sutures; close cuff anterior to posterior.

- Drain the bladder. Perform cystoscopy if prolapse/incontinence procedures performed.

- Send home in about five hours.

Here are two videos showing the technique. This first video (7 minutes) highlights the major parts of the technique with an emphasis on how to use the Ligasure safely. The concern for thermal injury has prevented many physicians from incorporating energy sealing devices into vaginal surgery, but patient outcomes have been consistently demonstrated to be equal or better when an energy sealing device is used. This video demonstrates the parts of the technique which maximize thermal safety:

The second video is the full length video (23 minutes) of the same surgery with step by step explanations and details of each step:

Ultimately, there is no right or wrong way to do a vaginal hysterectomy. However, if you cannot do the following, then you should consider converting to a different route:

- Make a posterior colpotomy.

- Take the uterosacral ligaments, cardinal ligaments, and uterine vessels.

The rest is creativity.

There are some things which have been traditionally taught that serve to make the case unnecessarily difficult. For example,

- Don’t make an anterior colpotomy first. In fact, don’t worry about making it at all. It is almost always easier to make a posterior colpotomy first. The anterior colpotomy gets easier and easier the later you do it due to more uterine descent; just make sure that you dissect the bladder off the anterior cervix and lower uterine segment. The whole case can be completed without ever making an anterior colpotomy in the normal sense.

- Don’t suture pedicles above the level of the uterosacral ligaments. Several studies show reduced pain and bleeding with energy sealing devices and several studies have shown its safety. It is actually the right way to do the surgery, not an optional way. Plus, it will greatly expand the number of patients who can safely have a TVH because using an energy sealing device requires much less vaginal space and uterine descent than traditional methods. Older physicians sometimes worry that younger physicians will not learn how to sew deep in the vagina if we make them dependent upon the Ligasure or similar devices. But, the reality is that these younger physicians are just never sewing in vaginas any more because they are not comfortable with vaginal surgery; using an energy sealing device may be the key to saving vaginal surgery. Sewing deep in the vaginal cavity is an important skill but it is also the perfect skill to be taught with simulation. In any event, patient outcomes are better with an energy sealing device, so let’s embrace the technology for our patients’ benefit.

- Don’t get married to any particular order of steps or methods. As long as you can make a posterior colpotomy, you can almost certainly do the case. But different sizes and shapes of uteruses sometimes require different approaches. Progress is progress. When you can’t make progress, convert.

- Don’t be afraid to to convert! There is no shame in converting. In the old days, a surgeon who converted his approach was viewed as less than competent, since he should have known the correct route in the first place. We can’t always know. But the fear of conversion has caused gynecologists to not tackle all but the most obvious, easiest, prolapsed uteruses. This is not the 1970s; don’t be afraid to convert.

There are few real contraindications to a vaginal approach. Still, there are some things that make a vaginal hysterectomy more difficult. Victor Bonney said in 1918,

The more one performs vaginal hysterectomy, the less contraindications one encounters.

Any skilled vaginal surgeon will whole-heartedly agree with Bonney. X. Martin et al. reported in 1999:

There is no absolute contraindication to vaginal hysterectomy. (Il n’y a aucune contre-indication formelle a l’hystérectomie vaginale.)

Still, there are impediments, whether real or psychological. Here are some:

- Lack of descensus/nulliparity/no prior vaginal delivery

- Prior cesarean/difficult anterior colpotomy

- Large uterus

- Obliterated posterior cul-de-sac

- Endometriosis

- Concurrent need for adnexectomy

- Obese patient

- Prior abdominal surgery

Here are some tip and tricks for each of these impediments:

Nulliparity and Lack of Descent

Agostini et al. in 2003 prospectively compared vaginal hysterectomy outcomes in 52 nulliparous and 293 primiparous or multiparous women. The mean operative time was significantly longer in nulliparous patients (95 vs. 80 minutes), but vaginal hysterectomy was successfully performed in 50/52 of the nulliparous and 292/293 of the parous patients, suggesting that nulliparous women can be considered candidates for vaginal hysterectomy.

Varma et al. in 2001 did a prospective study of patients without prolapse who underwent hysterectomy for benign conditions. There were 97 abdominal and 175 vaginal procedures, with no significant differences in patient characteristics. The frequency of complications was low and similar in both groups.

Tips for nulliparity or lack of descent.

- Doderlein-Kronig Technique (massage). Massaging the uterosacral ligaments while the cervix is under tension for a few seconds can provide as much as 1 cm additional uterine descent. I do this routinely on non-prolapse cases.

- Non-Trendelenburg positioning. Trendelenburg often artificially shortens the vaginal length by rolling the patient back on her buttocks, making the geometry more acute. The weighted speculum is drawn out slightly, so the length from the edge of the speculum to the uterosacral ligament is longer, making it more difficult to place a clamp.

- Staged uterosacral ligation. Life gets a lot easier after the uterosacral ligaments are ligated. You don’t have to get a perfect bite the first time. Use a right angle clamp if necessary to take smaller portions. Get what you can. In a non-descent case, it may take two or three bites on each side to get the uterosacral ligaments. Also, make sure you are getting the peritoneum in the clamp and cutting it entirely. It is very easy to miss it, and the uterus won’t come down until you do. A howardism: You can usually take two good bites in less time than one perfect bite.

- Non-traction approach (Purohit technique). Ram Purohit has developed a complete, non-descent, non-traction approach to vaginal hysterectomy. Videos of the techniques are available here. The basis of the technique is using right angle clamps to separate and seal tissue (while protecting the ureter) until the uterus can be artificially prolapsed.

- Don’t be scared of nulliparity. Often the nulliparous patient is easier than the obese, parous patient.

Prior Cesarean Deliveries/Difficult Anterior Colpotomy

Sheth et al. in 1995 performed a retrospective review comparing the vaginal hysterectomy outcomes of 220 women with prior cesarean deliveries (one or more) to 200 patients with no previous pelvic surgery. Only 3 of the 220 patients had inadvertent urological trauma intraoperatively. Factors favoring a successful vaginal approach were: only one previous cesarean, a freely mobile uterus, previous vaginal delivery, uterus not exceeding 10-12 weeks size, and absence of adnexal pathology. Infection following the previous cesarean was an unfavorable prognostic factor due to an increased risk of dense adhesions between the bladder and cervix. The authors concluded, “The vaginal route is the route of choice for performing a hysterectomy in patients with previous cesarean section.” I usually feel much more confident dissecting scarred bladders off of uteruses vaginally than abdominally.

Tips for the difficult anterior colpotomy.

- Attempt anterior entry only after posterior entry has been accomplished and uterine descent achieved after ligation of the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments.

- Sharp dissection. Don’t push your way into the wrong plane (or into the bladder); use sharp dissection until you are past the point of difficulty.

- Subfascial dissection. Better to leave behind a little uterine peritoneum than a little bladder; stay deep in cases of scarred-down bladders.

- Reverse Döderlein maneuver. In the Döderlein-Kronig technique of supracervical vaginal hysterectomy, an anterior colpotomy (only) is made and the fundus is delivered through it and then amputated from the corpus. In difficult anterior colpotomy cases, deliver the fundus through the posterior colpotomy then dissect down (as in an upside down abdominal hysterectomy, usually on your knees) until you can make an anterior colpotomy using traditional abdominal techniques.

- Transurethral uterine sound. Sometimes sharply bending a sound and then passing it through the urethra, pointing the curved tip down to the cervix, can help identify the edge of the bladder in a difficult dissection.

- Trans-cul-de-sac uterine sound. The sound can also be brought around the uterus through the posterior colpotomy (or in many cases a finger can be passed around, especially if upper pedicles have already been ligated).

- Uterine bivalving. Bivalving the uterus to make a posterior colpotomy is a well-accepted technique (see below). The same procedure can be used to make an anterior colpotomy; just make sure you are staying intrafascial.

- Full versus empty bladder. The only benefit of a full bladder is that you can see urine come out when you injure the bladder, but the full bladder likely increases the risk of bladder injury. Keep it empty in most cases.

- Indigo carmine, sterile milk, dilute methylene blue, pyridium, or other dyes. Backfilling the bladder with a dye (or giving the medicine IV or PO as the drug requires) can help identify injuries. Identifying an injury when it happens is essential to not making matters worse. Don’t be afraid of injuring the bladder. Cystotomy at the time of anterior colpotomy is relatively rare and easily fixable.

- Adhesions of the bladder almost always occupy the middle 3/5 of the cervix, not the lateral 1/5s. This fact was demonstrated by Sheth and is very useful. Always start laterally with dissection around scarred bladders, moving upwards and medially. This may allow you to create an opening through the lateral uterocervical broad ligament space and go around the adhesion.

- If an obstructing fibroid is in the anterior wall, remove the fibroid then attempt anterior entry.

- For many people, the anterior colpotomy is the most difficult portion of a vaginal hysterectomy. I think this partly stems from a poor understanding of the relevant anatomy. This article by Sheth is one of the best things available to read if you are struggling.

Large Uterus

Sizzi et al. in 2004 performed a prospective study that evaluated vaginal hysterectomy outcomes in 204 consecutive women with a myomatous uterus weighing between 280 to 2000 g. Vaginal morcellation was performed in all cases. No patient had uterovaginal prolapse. Four patients underwent conversion to a laparoscopic procedure for the completion of the hysterectomy (two of these ultimately required laparotomy). Adnexectomy was successfully performed vaginally in 91% of patients in whom it was indicated. The authors concluded that traditional uterine weight criteria for exclusion of the vaginal approach may not be valid.

Expert vaginal surgeons are quite comfortable in removing larger uteruses vaginally. There is an informal “kilo club” of vaginal hysterectomists who have removed uteruses weighing more than a kilogram (no longer an uncommon feat) and I have even heard of a “two kilo club,” but have yet to join it. The key is morcellation. Taylor et al. in 2003 showed that vaginal hysterectomy with morcellation provided better outcomes for uteruses up to 1 kilo than did abdominal hysterectomy. There are several methods for morcellation:

- Bivalve. Cut the uterus in half from 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock as high up as you can safely see to cut.

- Coring. Take out circular sections of tissue held under tension to debulk the uterus.

- Paper Towel. Staying intrafascial, continuously “roll” out longer and longer sections of uterine tissue (helpful for adenomyosis).

- Wedging. Excise triangular wedges of uterus from either the anterior or posterior wall.

- Myomectomy. Remove fibroids as they are encountered using traditional myomectomy techniques.

Tips for morecellation.

- Better instruments. Use Leahy-type clamps, tumors clamps, heavy scissors, Vulsellum forceps, Jorgensen scissors, and other instruments not normally on the TVH tray. The right instruments makes life a lot easier. Using the Jorgenson scissors has two benefits for morcellation: they are usually very sharp, and they are sharply curved.

- Start by bivalving the uterus from 12 to 6 o’clock.

- After bivalving, use combinations of wedging, coring, and myomectomy. Always stay intrafascial and always know where you are in relationship to the uterine walls.

- The “paper towel” method works best for large, adenomatous uteruses.

- Often the scalpel is the best tool for morcellation, but be careful: always know what you are cutting. NEVER use a mechanical morcellator vaginally.

The Obliterated Posterior Cul-de-sac/Endometriosis/Difficult Posterior Colpotomomy

A truly obliterated posterior cul-de-sac is rare and is most often associated with stage 4 endometriosis or prior pelvic infections. Difficult posterior colpotomies in the absence of adhesions are rare and usually the result of dissection in the wrong plane (usually too close to the cervix). Most patients who undergo hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain or advanced endometriosis have had prior diagnostic laparoscopies so that an obliterated cul-de-sac is hopefully not a surprise. Another strategy for preoperative detection of an obliterated cul-de-sac is a vaginal ultrasound, applying the visceral slide adhesion imaging technique to the cul-de-sac. I have found this almost universally feasible. A thorough preoperative exam is very helpful as well, either in the office or under anesthesia.

If the posterior cul-de-sac is obliterated, then consider:

- Laparoscopic-assistance. The LAVH for treatment of advanced (stage 3 or stage 4) endometriosis is probably always a good idea, both to aid with obliterated cul-de-sacs but also to treat extrauterine disease.

- Döderlein maneuver. In a patient with appropriate descent (usually para 2 or greater), the anterior colpotomy can be performed first and then the uterus delivered through the colpotomy using the Döderlein maneuver. After taking the upper pedicles, it is usually easy to dissect bowel/rectum off the posterior wall of the uterus until the colpotomy can be made. The fundus of the uterus can be removed (completing the supracervical procedure) to make room, and if severe adhesions exist, the case can be completed as a subtotal vaginal hysterectomy.

- Intrafascial dissection. The posterior colpotomy doesn’t absolutely have to be made. Careful intrafascial dissection, stripping the uterus of its peritoneum, can be performed, bypassing the points of adhesion.

If the cul-de-sac is not obliterated, but posterior colpotomy is difficult, then consider:

- The Pelosi method. This involves making a vertical incision at 6 o’clock on the cervix and continuing this incision (like a partial bi-valving of the uterus) until a posterior colpotomy is made, since eventually the incision will run into the reflected peritoneum.

Need for Adnexectomy

Multiple studies show a > 95% success rate in vaginally removing ovaries (or fallopian tubes alone). Davies et al. in 2003 were successful in 97.5% of cases. Need for concomitant oophorectomy should be rare, if evidence-based decisions are made. Prophylactic salpingectomy is controversial at best, but virtually all tubes can be removed vaginally if desired (it is easier to remove a tube than an ovary).

Obesity

Isik-Akbay et al. in a 2004 study concluded that vaginal hysterectomy was the superior and preferred approach for obese women, with a lower incidence of postoperative fever, ileus, urinary tract infection and shorter operative time and hospital stay. Exposure of the operative field can be difficult in obese women, regardless if an abdominal or vaginal route is taken. I, for one, would much rather “struggle” at a vaginal hysterectomy of a morbidly obese woman than struggle with exposure at an abdominal hysterectomy in the same patient. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with obese women is often no easier, introducing new challenges like degree of safe Trendelenburg, length of instrumentation, safe ventilation, etc.

Tips for obese patients.

- Use candy cane stirrups. Candy cane stirrups are inherently safer than “yellow-fin” style stirrups, which are associated with more nerve injuries. Get the legs up and out of the way.

- Allow the buttocks to drape off the table. Having the buttocks even a couple of inches beyond the break of the bed makes a big difference in straightening out the vagina and making the distance from speculum to cervix shorter.

- Avoid Trendelenburg’s position. As discussed already, Trendelenburg’s position changes the geometry in a negative way.

- Don’t worry if the weighted speculum doesn’t fit. Sometimes the short speculum is too short and the long speculum is too long (or even too short). Sometimes the angle of the speculum is too acute. Most weighted specula can be bent a bit and making a more obtuse angle may help. Angle-adjustable weighted specula are also commercially available. You can always use a narrow Deaver retractor or even a Heaney retractor instead of a weighted speculum.

Prior Abdominal Surgery

Prior abdominal surgeries are an indication for the vaginal route. Avoid the risks of trocar placement in women with prior GI surgeries by using the vagina as an access route to the abdomen. We have already discussed mitigation of anterior bladder adhesions or the obliterated posterior cul-de-sac.

Other types of adhesions may be encountered. Women who have had prior cesareans may have adhesions of the anterior uterus to the anterior abdominal wall. This may be suspected intraoperatively by noting Sheth’s cervicofundal sign, which occurs when pulling on the cervix depresses the anterior abdominal wall. These type of adhesions are often the most difficult to manage but can usually be handled with sharp, intrafascial dissection. Laparoscopic-rescue might be necessary in severe cases.

Adhesions of small bowel or omentum are usually easily managed with direct dissection after artificial prolapse of the uterus (and more easily handled with a pair of Metzenbaums than with a laparoscope).

What Else?

The biggest contraindication to vaginal hysterectomy is a lack of experience, confidence, and enthusiasm by the operator. I have listed only a few brief tips and tricks. The truth is, most “difficulties” encountered are made phenomenally easier by using a thermal sealing device, like the Ligasure. This allows the surgeon to much more easily combat a lack of uterine descent and have confidence in the security and hemostasis of the uterine blood supply, greatly expanding the number of cases that are amenable to standard techniques. In the 1970, Robert Kovac showed that over 80% of uteruses could be removed vaginally by gynecologic residents, using the then available standard techniques. Simplified vaginal hysterectomy using Ligasure offers even more promise and easier, safer cases.

A Few More Points

There are few other things that we should do around the time of hysterectomy to ensure best outcomes.

- Prescreen patients for bacterial vaginosis (at least by history if not exam) and treat prior to surgery.

- Universal preoperative administration of prophylactic antibiotics.

- Create a culture, expectation, and protocols which emphasize same day discharge. Most patients can go home within a few hours. Zakaria and Levy in 2012 reported on 1,162 cases of vaginal hysterectomy with a median operative time of 34 minutes. 96% were discharged home on the same day. Only five patients required readmission or emergency room evaluation within the first 30 days. My experience over several hundred cases has been similar.