In Part 1, we examined the evidence that indicates that there is an increasing cesarean delivery rate with an increased rate of induction of labor, particularly among women with unfavorable cervices; consequently, we also anticipated an increased rate of maternal mortality and severe morbidity. Next, we must determine what the real benefit of earlier induction is to fetuses. How many intrauterine fetal demises (IUFDs) are saved by ending pregnancies up to two weeks earlier (at 39 weeks rather than potentially 41 weeks)?

Between 39 and 41 weeks, it is generally agreed that there is a nadir of neonatal morbidity and mortality. This has driven our desire in the last decade to limit deliveries before 39 weeks and eliminate deliveries after 41 weeks. Of course, neonatal morbidity and mortality is measured only among surviving neonates; this means that IUFDs are not accounted for in this metric. Therefore, inducing a woman at 39 weeks would categorically decrease the number of IUFDs that occur after 39 weeks. It is this number of IUFDs that our debaters want to salvage with earlier induction.

So there are two questions that need to be answered.

- First, How many IUFDs occur in these two weeks, that is between 39 and 41 weeks gestation?

- Second, Are we just moving losses from one category to the next? In other words, if we decrease the number of IUFDs in the period, will there be a subsequent rise in neonatal deaths?

The answers to both of these questions are very difficult due to the rarity of these events. These are not questions which are amenable to randomized trials. The number of enrolled pregnancies needed in such a trial to actually make a conclusion with statistical confidence is excessively high. Drawing assumptions from populations of women who were induced at 39 weeks for medical reasons (such as hypertension or diabetes) isn’t fair either; the IUFDs which are prevented in a population of diabetic women, for example, are typically fetuses who died of a maternal issue such as maternal diabetic ketoacidosis. We have no reason to think that there was anything inherently wrong with those fetuses. Yet the low risk patient, perhaps a healthy 19-year-old primigravida with no medical problems, who doesn’t smoke, who has normal weight gain during pregnancy, who has had normal prenatal testing, who feels a vigorously kicking baby with no known complications, and whose cervix at 39 weeks is still closed, thick, and high – this is the woman we need to understand more about regarding this debate. What is her risk of fetal demise in the next two weeks, measured against her risk of cesarean delivery with induction?

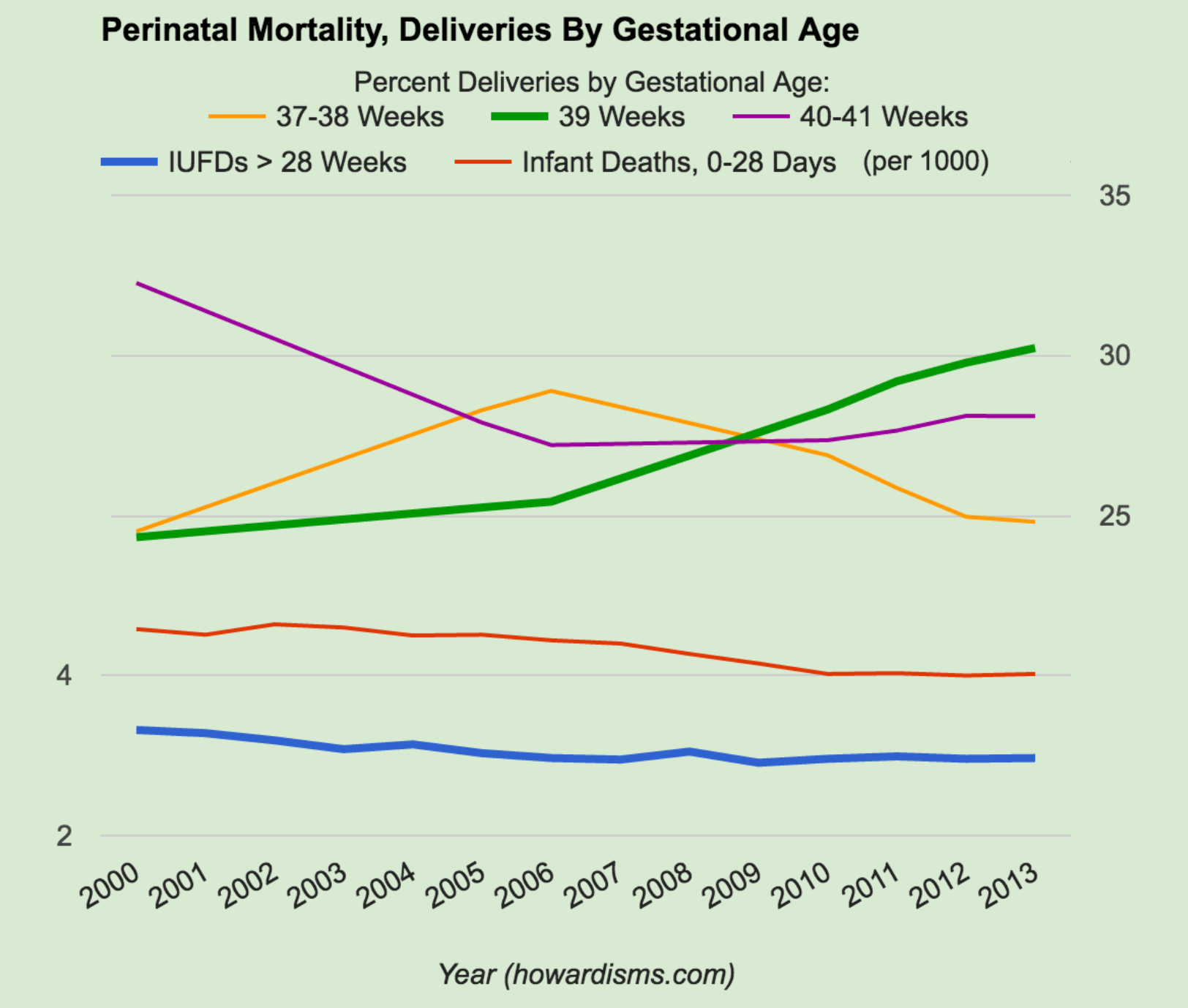

Over the last decade, starting in about 2006, the number of women delivered at 39 weeks (or later) has increased, while the number of women delivered at 37-38 weeks has decreased. The preterm birth rate has also declined in this time period. Yet the number of IUFDs after 28 weeks of gestation has remained the same. One would expect this number to increase as the average gestational age of women delivering in this group has increased; nevertheless, it has remained steady at just under 3/1000. This defies the logic that delivering earlier will make a measurable difference in the number of IUFDs. By our debaters’ rationale, we should have witnessed an increase in the number of IUFDs as women have stayed pregnant longer.

So why has the number of fetal losses not increased as women have stayed pregnant longer? Likely because we, as a speciality, have also become better at identifying high risk patients who should be delivered earlier and have delivered them accordingly (diabetics, preeclamptics, cholestatics, pregnancies with oligohydramnios or severe growth restriction, etc.). At the same time, we have not been delivering low risk pregnancies as early, often for patient or provider convenience.

Norwitz himself, during the debate, admits that there is a “failure to identify underlying risk factors” leading to IUFDs. But clearly we have made progress in the last decade since women are staying pregnant longer without an apparent increased risk of fetal demise. MacDorman et al in December of 2015 came to this conclusion in the Green Journal after careful consideration of the data. Little et al in the same issue, using a different approach, reached the same conclusions.

But, of course, depending on the agenda one wants to advance, the same data can be used differently. In the May 2016 Gray Journal, Nicholson et al concluded that the term stillbirth rate had increased in the same time period, and accounted for as many as 335 additional stillbirths in 2013 compared to 2007. He responded to the articles by Little and MacDorman in a letter to the Green Journal, clearly showing his bias and aplomb that they did not reach his conclusion. The argument is essentially that there just has to be more IUFDs because IUFDs will happen in the 38th week of gestation if women are still pregnant then. While this is unequivocally true, the actual numbers are the real debate. If we have kept the rate of fetal loss the same (by filtering out high risk pregnancies), then the question is, What is the rate of IUFDs at 39-41 weeks among lower risk women? It is hard to argue with Norwitz’s statement, “If a baby is born at 39 weeks, it’s not at risk of stillbirth at 40 weeks.” But the rate of stillbirth is likely much lower than Nicholson and others would care to admit (though, granted, it is not zero).

Silver and MacDorman replied to Nicholson et al and made the following eloquent point:

Reduction in stillbirth is a passion that we all share. The problem with delivery as a global strategy to reduce the risk of stillbirth is the risk of preterm birth. Even late-preterm and early-term births cause increases in short-term and long-term morbidity and mortality. Accordingly, we need to balance the risks of stillbirth against the risks of preterm birth. Cost of interventions, maternal anxiety, and harm from false-positive tests also must be considered as we optimize stillbirth-prevention strategies. Obstetrics is rife with examples of good intentions leading to harm.

Thus, we must try vigilantly to appreciate the real benefits of the strategy of earlier induction weighed against real harms. Let’s summarize what we do know so far.

- From 2006-2013, the number of babies dying in the first 28 days of life has declined, from about 4.44/1000 to 4.02/1000 in 2013. Could this be the result of fewer cases of iatrogenic prematurity, due to our previous habit of delivering women earlier? It may certainly contribute to the picture; though, in fairness, we have no way of knowing how much it contributes. It stands to reason that we are just better at neonatal care today than we were ten years ago, regardless of gestational age.

- Total perinatal losses, from 28 weeks of gestation to 28 days of life, have declined significantly in the last decade as women are delivering later in pregnancy, not earlier.

- In 2006, 52.6% of women were delivered at 39 weeks or later, with 28% of women delivered at 37-38 weeks.

- In 2013, a total of 58.33% of women were delivered at 39 weeks or later, with only 24.8% of women delivered at 37-38 weeks.

- In the same time period, perinatal mortality (as defined above) declined by 0.42/1000.

So what is the stillbirth rate in the 39th and 40th weeks? Based on data from 1989-1991 in England, Hilder et al estimated the rate of IUFD from 39.0-39.6 weeks as 1:2039 (0.49/1000), and from 40.0-40.6 weeks as 1:1148 (0.87/1000). (For comparison, the rates from 37.0-37.6 were 1:3332 and from 38.0-38.6 were 1:1922). I would suggest that these rates likely represent an upper limit, since the data are nearly 30 years old and we have improved our identification of high risk patients who are delivered before these gestational ages. However, they are not in a US population.

MacDorman estimated these rates (in 2015) to be 0.82/1000 in the 39th week and 0.87/1000 in the 40th week in a US population. Overall, McDorman’s numbers are higher than Hilder’s. Hilder’s numbers offer promise that with improved identification of high risk pregnancies, we might lower the loss rate in the US.

There are roughly 1.2 million deliveries per year in the 39th week and about 1.1 million deliveries in the 40th week in the US. Using MacDorman’s numbers, this translates into 984 IUFDs in the 39th week and 957 in the 40th week. The actual numbers are hard to determine and there are tons of methodological errors involved in using calculations like these. Also, some of these IUFDs happen in labor (meaning that they would not have necessarily been prevented by an earlier labor). We don’t know the real rates. Some of the IUFDs in these gestational ages are likely reported with the wrong gestational age (with some pregnancies being earlier or later with poor dates). Many occur in women with no prenatal care (or women who have intended home births), so that there was not an opportunity to intervene on a high risk condition.

Thus, it’s difficult to really know, but at most there are probably about 1,500 IUFDs each year that might be prevented with routine delivery at 39 weeks out of 2.3 millions births. The number might be substantially lower. These numbers are based on huge assumptions about data that we don’t really understand. Also, there are strategies that the debaters have not considered:

- Why not suggest delivery at 40 weeks? That would seem to cut the number of IUFDs, whatever it is, in half, while at the same time dramatically reducing the number of inductions and the correspondent increase in cesareans and cost compared to the delivery at 39 weeks strategy.

- Why not suggest delivery at 38 weeks? For a very minor increase in short-term neonatal morbidities, our debaters would potentially save another 500 IUFDs or so. Why do they think that the relatively minor increase in RDS isn’t worth this benefit? Nicholson clearly does. There are those who advocate delivery of all babies at 37 weeks for this same reason. But our debaters know that with the earlier strategy we will definitely see an increased risk of neonatal death that cancels out any benefit.

- Why not suggest improving our identification of women who would benefit from earlier delivery to maximize the benefit from early induction while shying away from low-risk nulliparous women and/or women with unfavorable cervices? There are numerous ways of carving out higher risk groups, such as obese women, black women, women over 35, etc. Black women, for example, have nearly double the risk of IUFD in the 39th week as do white women. The data seems to best support this last point as a strategy to reduce the number of unnecessary IUFDs while not increasing even more the risk of death among mothers.

The proponents of earlier induction point out that there are 26,000 or so IUFDs in the US every year, but the vast majority of these occur well before 39 weeks. Thus, delivery at 39 weeks barely makes a dent in this scary number. Yet increasing our efforts at identifying high risk patient populations and focusing our efforts would like likely benefit a much larger range of gestational ages with an even greater mortality benefit.

Also, let’s remember the cost of the 39 week delivery strategy. In Part 1, we estimated an increased risk of 575 maternal deaths to fully implement such a strategy, and this is likely a conservative estimate as the rates of abnormal placentation in our population would grow dramatically with an increased cesarean delivery rate. I would suggest that a selective strategy of focusing on women most at risk (and OB/Gyns more carefully obeying our labor management guidelines) can reduce both the number of fetal and maternal deaths from current rates. Let’s not treat the low risk, first time mother the same way we treat a high risk pregnancy.

We also don’t really have the data to know if the neonatal loss rate would increase with the 39 week delivery strategy. There is evidence to suggest that it would. Remember, the neonatal loss rate has fallen by 0.42/1000 as we have only slightly increased the proportion of women delivering at 39 weeks over the last ten years. If delivering women earlier increased this even 0.25/1000, that would increase the number of neonatal deaths by 1,000 per year. We have to be careful to not assume that a fetus who dies in utero would not have died as a newborn if born alive. There are dozens of potential fetal issues that remain present in the neonatal period and contribute to neonatal losses, and we run the risk of adding iatrogenic prematurity to these problems. Shifting mortality from one category to another accomplishes nothing.

Two issues remain.

First, what impact would earlier delivery of 2 million women in the US have on cost, bed utilization, etc. We would likely add many millions of bed-days to the cost of giving birth in the US and many billions of dollars. Who is harmed by spending these excess resources? Where better can we spend the money and time to have a greater impact? How many lives would be lost due to reallocation of already precious and scarce resources? Also, how many more women would consider having home births in order to avoid the over-medicalization of the birth process? How would even a modest increase in home births negatively affect the perinatal and maternal deaths that must be considered in this equation? And would we increase the mortality of women who have vaginal deliveries, by increasing the rates of thromboembolism and hemorrhage associated with induction of labor?

Second, whose life is more valuable, the life of a fetus or the life of a mother? No one wants to answer this question or even think about it really. But this is a question that must be answered to balance the risks and benefits of this debate. I would suggest that when all factors are accounted for, it’s roughly an even trade for one or so maternal deaths to save one or so fetal deaths. But what if it’s not 1:1? Maybe it’s one mother for two fetuses. Then what? It has been a hallmark of Obstetrics that the life of the mother is more valuable than the life of a baby. A young woman with 3 young children at home offers more to her family and to society than a child with a questionable survival. It’s not mean to say, it’s just true.

In Part 3, we will consider some other ancillary issues to this debate and have some fun.