The practice of breastfeeding is as old as, well, mankind. Few functions could be considered more natural, and few biologic functions work as well. It works so well that until recent history, literally every child in human history was breastfed (though sometimes by wet nurses). Wet nurses have been necessary throughout human history when the mother could not breastfeed, often due to death during delivery or some other condition. In some rare cases, healthy women just couldn’t produce adequate milk.

But from the 1880s to 1950s, breastfeeding saw a dramatic decline, and by the 1950s, breastfeeding was considered something that only an uneducated or poor woman would do. Why?

For starters, breastfeeding became the less fashionable thing for women to do if they had the money to not do it. Aristocratic women often hired wet nurses so that they wouldn’t have to do the act themselves, and it became a status symbol to not breastfeed, even in late Renaissance times. A woman who forewent breastfeeding could continue to wear fashionable garments and participate in activities that otherwise might be difficult, and myths arose about breastfeeding that further made it unpopular among these classes, like the myth that breastfeeding might ruin a woman’s figure.

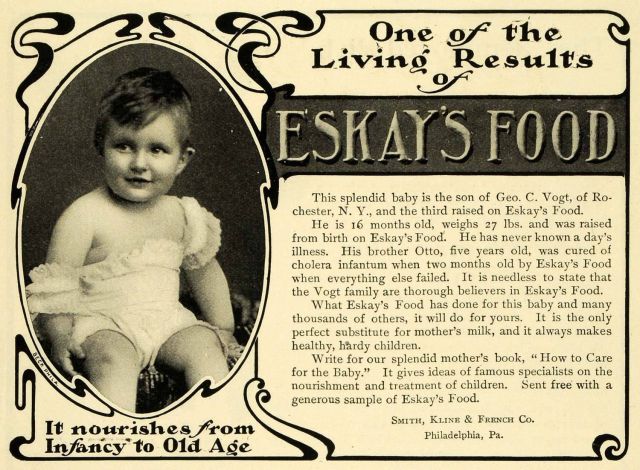

By the start of the 20th century, the idea that the most fashionable and elite would not deign to breastfeed promoted the societal belief that breastfeeding was a thing for the poor and ignorant. By 1900, wet nursing had been replaced by bottled animal’s milk, and became affordable for the lower classes. In 1865, Liebig’s formula, a mixture of animal milk, wheat and malt flour, and sodium bicarbonate became available. It was touted as the ideal food for babies; perhaps it is ironic that it was called Liebig. Eventually, formulas based on Borden’s evaporated milk became available too, making formula a more readily available and storable commodity. There were 27 patented brands by 1883. The American Medical Association eventually started to give a seal of approval to such products, and by the 1950s, physicians and consumers believed that formula milk was a safe and perhaps more effective substitute for breast milk. This, combined with the perceived status of not breastfeeding, let to widespread adoption and continued decline in the rate of breastfeeding into the 1970s.

There has been a resurgence in breastfeeding in the last 30 years, but breastfeeding rates that were over 90% at the start of the 20th century are just over 40% today.

Breastfeeding is a great illustration of the principle of reaction and overreaction that I talked about here. The “normal” for millennia was that women breastfed their children, and in rare circumstances, another woman breastfed for them. Failure to breastfeed was unusual, and real problems with breastfeeding were uncommon. Then, due to a fad, women were financially exploited and an industry grew up which all but replaced breastfeeding. This industry was supported by doctors, who, particularly in the 1950s, believed that they were smarter than nature and could use science to make a more perfect mechanism of human reproduction. Finally, women realized that they were being had and developed an over-reaction to formula feeding.

In the over-reaction, breastfeeding is not the norm, but its the answer, in and of itself, to almost every problem facing modern society. It not only nourishes babies, but it makes them smarter, less obese, immune to infectious diseases, less likely to develop diabetes or Crohn’s disease, less likely to die of SIDS, lessens postpartum depression, halts global warming, is excellent birth control, and the moms will lose weight without even trying. Almost every benefit I just listed is either a lie or greatly exaggerated. As is often the case, when over-reaction biases the science, then the benefits get exaggerated and the harms reduced. High quality, controlled studies have failed to demonstrate almost all of these claims. There is no good scientific evidence that children are smarter or do better in school, for example. Breastfeeding does improve children’s immune systems for a short time, but the magnitude and length of effect is small. There is no firm scientific relationship to subsequent development of diabetes, SIDS, celiac disease, or Crohn’s. Women who breastfeed, in fact, do not lose more weight than women who bottle feed. I could go on, but I am not trying to argue that women shouldn’t breastfeed; they should. But the cause of breastfeeding is not helped by lying about or exaggerating its benefits.

The question I actually want to ask is, When did breastfeeding become a disease?

The women who led the charge to reclaim breastfeeding in the 1970s and 1980s are, in large part, the same women who also desired to retake natural birth. They hated how birth had been turned into a disease and over-medicalized: too many cesareans, too many episiotomies, too many interventions. They wanted birth to return to a simpler time, with interventions used only when necessary. In the same way, they rebelled against formula makers and the assertion that we had outsmarted a woman’s breasts when it came to feeding babies.

Yet, today, a whole industry exists that has over-medicalized breastfeeding, treats it as a disease, offers far too many interventions, and has even offered a new savior that will improve the process of babies suckling their mothers breasts. What is this industry? Lactation consultancy.

Here’s how the con works. First, you oversell the benefits of breastfeeding. Next, with women’s anxiety peaked about the cost of breastfeeding failure (who wants a dumb kid, after all?), then you take the normal pitfalls and difficulties of pregnancy and turn them into a crisis. Finally, you stand ready to offer a variety of non-evidence-based but lucrative interventions to help them make it through.

In the current environment, the breast pump is the new cesarean delivery, herbals are the new episiotomies, and exaggerated claims of benefits are used to create an environment of fear that encourages over-utilization of these interventions. Perhaps I’m being unfair. I’m not. Let’s look at some examples.

Galactagogues

A variety of agents are frequently recommended to promote milk production in women who complain of decreased milk, including metoclopramide, domperidone, shatavari, fenugreek, silymarin, garlic, Asparagus racemosus, milk thistle, oxytocin, goat’s rue, beer, medicago sativa, alfalfa, Onicus benedictus, blessed thistle, Galega officials, brewer’s yeast, and malunggay. None of these, with the exception of domperidone, have scientific evidence of efficacy, and the risks of domperidone usage likely outweigh the small magnitude of effect. The scientific literature does not support the use of herbal galactogogues at all. These often expensive and ineffective remedies are promoted without a single shred of scientific evidence of suggestion of efficacy. Decreased milk volume is treated with reassurance, patience, encouragement of hydration, and increased feeding frequency.

Engorgement

Breast engorgement is a common and frequent problem for breastfeeding women. It is usually self-limited, lasting five days or less. A variety of interventions are offered, including cabbage leaves, acupuncture, acupressure, cold-packs, massage, etc. No quality evidence exists for any of these interventions. There may be some benefit from hot and cold packs, massage, and other interventions that offer anti-inflammatory benefits, but no quality data exists even for these recommendations. Some advice is actually harmful, like laying on the back for prolonged periods (which would undoubtedly increase the risk of thromboembolism, particularly in women who had a cesarean). The best advice: continue to feed the baby every 2-3 hours, where a tight-fitting bra, use Tylenol or other pain reliever if it is too painful, and consider hot showers or cold packs. In others words, continue with normal breastfeeding behaviors and it will pass.

Breast pumps

Breast pumps have become the utility player for lactation consultants. Can’t make enough milk? Pump. Engorged? Pump. Can’t get a good latch? Pump. Nipples hurt or bleeding? Pump. But breast pumps are not a good thing. Women who pump, for whatever reason, are less likely to continue providing their child breast milk. The earlier the pump is used, the worse the outcome. Women are often anxious in the first two weeks or so about how much volume of milk they produce; they are tempted to supplement or to do something, anything, to improve their own milk volume. Pumping is often recommended. While a woman is still in the hospital, these anxieties may be piqued; a nurse or pediatrician may tell the mother that her baby has, for example, lost 8% of its birthweight and that they will be keeping “an eye on it.” For a woman barely producing colostrum, this harkens feelings of inadequacy and failure. A more supportive statement might have been, “Your baby’s weight was good today! Everything is going great!”

Breast milk production and let-down is largely a hormonal event; the cry and stimulation of a hungry baby is the most effective agent we have for coordinating these hormones. Somehow, the laborious hum and whir of a breast pump doesn’t quite have the same effect. The most perfect tool ever designed for evacuating milk out of a swollen human breast is the complex suckling technique of a baby. The conical vacuum suck of a breast pump is far inferior. Babies need a few days to learn the intricacies of suckling, and sometimes they need the motivation of hunger to get it right. Babies will always take the path of least resistance; if given the chance, they will gladly take the easy flow of milk from a bottle nipple over the work needed to harvest it from momma. This is called nipple confusion. Once a new baby is introduced to the easy way, they will scarcely and with difficulty return to the hard way.

Nature got it right. You will make milk because your baby will stimulate you to do so, and your baby (almost always) will become effective at feeding. Patience is required for the first few days, as colostrum turns to milk and milk turns to lots of milk. The only intervention required is patience and reassurance.

Pumps may be useful for babies with a cleft lip or palate or other abnormality, or for extremely preterm babies; but these situations are rare. Pumps are a necessary evil for when women return to work and are otherwise apart from the baby, but this usually happens after the baby has learned to feed well and the milk supply is well established. There is no scientific evidence that early use of the breast pump to support breastfeeding is effective.

Birth control

When milk volume seems to drop off is when women return to work (about 6 weeks after delivery). A lot changes at this time. They may now be pumping, and this is less effective at stimulating milk production. The baby may still develop some nipple confusion, further compounding the issue. The baby may be sleeping better throughout the night and feeding less thoughout the day, resulting in fewer feedings; and busy mothers at work may not be adequately hydrating. These events will often lead to a call to the lactation consultant for advice, where galactagogues, higher-powered pumps, and other non-evidenced based advice will be given. But one key question will be asked, “Did you start any birth control?” Of course, most women have started birth control at about the time they return to work, so birth control is immediately offered as the reason for breast milk failure.

- Immediate (or delayed) use of the Nexplanon does not affect breastfeeding volume.

- Neither the hormonal IUDs nor the copper IUD affect breastfeeding.

- The use of combined oral contraceptives does not affect breastfeeding volume or breastfeeding continuation rates.

Stop blaming the birth control! We haven’t believed that OCPs affect breastfeeding since the 1970s, at least in the scientific literature. What we do know is that these methods of contraception are all superior to lactation amenorrhea. I have delivered several babies because a lactation consultant repeated incorrect advice from forty years ago.

I could go on. Many lactation consultants offer advice for transient problems; since the problem is transient, then whatever strategy is suggested works. This then provides positive feedback, and the collection of suggested remedies becomes larger and larger. This is the basis of all anecdotal medicine: you can treat almost any self-limited condition without almost any intervention with success.

So breastfeeding is not a disease. Stop treating it like one.

Before I get too carried away, I should tell you that some of my favorite people in the world are lactation consultants. Many do a wonderful and irreplaceable job of helping women become milk-pros. Here are some benefits of a good lactation consultant:

- They provide comfort and assistance.

- They provide education.

- They provide reassurance to nervous moms.

- They help women understand which problems are normal experiences versus diseased states (mostly the baby not eating well as evidenced by urine output, stools, and weight gain or loss or mastitis).

- They understand that pumping is only required when mom is separated from baby. The mom may need education regarding proper handling, storage and administration of pumped milk.

- They provide comfort measures regarding engorgement (encourage the baby latching, acetaminophen, expressing milk sparingly, only if engorgement is unbearable).

- They provide education regarding how to properly clean bottles/pump equipment.

- They provide comfort measures regarding sore nipples (breast shells, nipple shields).

- They give assistance with proper latching of a newborn or positioning for the mother’s comfort.

- The give assistance and education with proper supplementation with formula if it is required.

Breastfeeding is a normal process and lactation consultants, more than anything, should normalize the process and encourage it, not treat it like a disease.

Here’s some evidence-based advice about breastfeeding if you’re a new mom.