I think a lot about how and where doctors get the information that informs how they practice medicine. In medical school, doctors learn information in the basic sciences that is often a few years out of date. They usually have too much belief in the principles they learn in the basic sciences, because that information is usually not presented with any indication of the level of evidence that supports the theories. This means, unfortunately, that many physicians spend their entire careers believing that the principles they’ve learned in the basic sciences are unchanging and infallible – barring some new and major discovery.

In residency, physician again learn information that is perhaps current and up-to-date or perhaps woefully out of date and archaic. Usually, no distinction is made between these two types of information. It seems most physicians are reticent to change learned practices after graduation from residency. The skill and quality of new physicians tends to peak just three or four years after graduation when they have gained sufficient confidence to apply what they learned in residency. After this initial period, in most cases, there begins a long and gradual drop off as those same physicians do not update their skills, attitudes, and knowledge. Knowledge and skills that may have once been relevant and reasonably up-to-date become increasingly irrelevant and bad practice. What’s worse, after just three or four years into practice, most physicians have little accountability. They are no longer worried about obtaining board certification or impressing senior partners, and they are comfortable in their daily practice patterns, so they are also not prompted by the anxiety of independent practice to study on a regular basis.

With no incentive to study systematically anymore, physicians get their information very casually and ad hoc.When a physician starts independent practice, they may participate in CME events of varying quality and importance, they may browse through the journals that are relevant to their field and occasionally read the abstracts of articles that pique their interest, and they may learn new information from colleagues. Yet, an alarming number of physicians learn new information in the same way that their patients learn new information: from news stories and pharmaceutical commercials. They also get their information, perhaps even most of their information, from sources that are carefully constructed to take advantage of the non-systematic way in which physicians learn – pharmaceutical and product representatives and industry-sponsored “throw away journals.”

These so-called “throwaway journals” are usually free, flashy, and concise. This means that they have a large audience, they quickly garner the readers’ attention, and the message is succinctly delivered so that even those physicians with short attention spans will consume the information. Important studies and articles from other publications are abridged, giving the editors the ability to present it however they wish. Most of these journals also include effective social media marketing, and the cost of production and marketing are generously supported by advertisers. These advertisers spend money because they know how effective it is at influencing physician practice.

One of the most important throwaway journals in Ob/Gyn is Contemporary OB/GYN. The featured article on this week’s email blast is entitled Homeopathy for endometriosis pain? The article is written by Cheryl Guttaman Krader, who writes for several such journals in different specialties. She is not a physician. The article is a review of a recently published study in the journal Homeopathy. She reports,

Potentized estrogen is an effective treatment for reducing endometriosis-associated pelvic pain (EAPP) that has been refractory to conventional hormone therapy, according to the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study reported by researchers from Brazil.

The next five paragraphs explain the methodology and results of the study without any commentary. She then explains that homeopathy works by the principle of similitude and for this reason 17-beta-estradiol was chosen as the homeopathic preparation because women who use the hormone suffer symptoms similar to those of “endometriosis syndrome.” Not one word of the report includes any potential criticisms or even hints at the fact that homeopathy is considered pseudoscientific quackery. There is no analysis of the methodology of the study or critical commentary. The only affirmative statement is the statement I quoted above: that a homeopathic preparation of estrogen is effective at treating refractory pelvic pain due to endometriosis.

This should be shocking to you that such an article appears in arguably the most influential journal for obstetricians and gynecologists. The original article in the journal Homeopathy is given credibility by this publication. This publication will lead to many OB/GYNs who are so inclined to begin using homeopathic estrogen as a treatment and so the vicious cycle of quackery and pseudoscience continues.

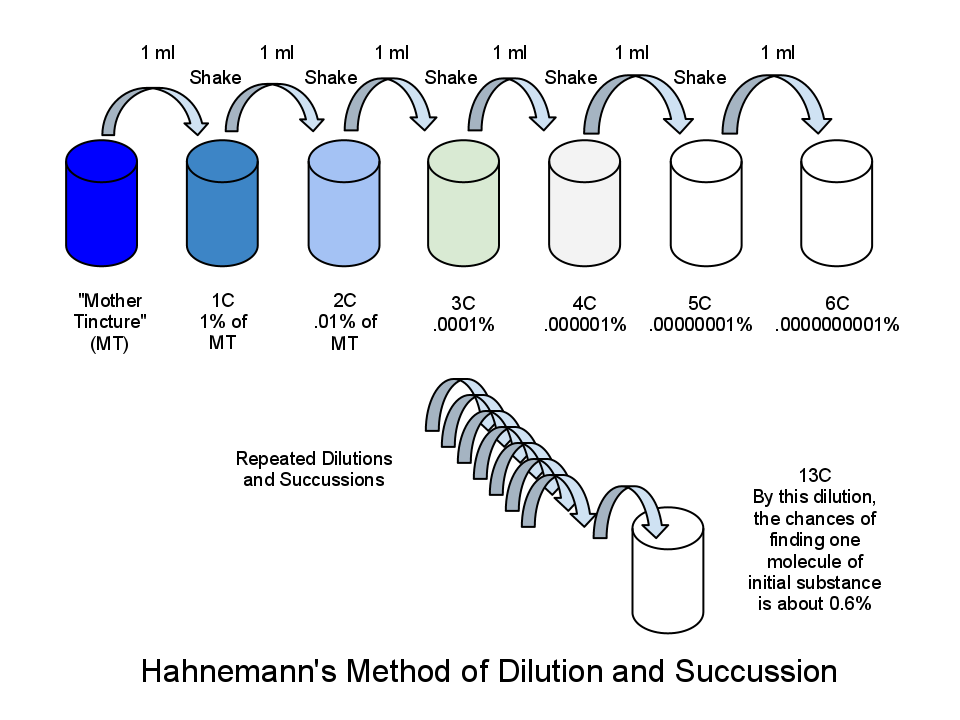

If you’re not as upset about this as I am, then you just don’t know anything about homeopathy. In this study, a homeopathic preparation of 24C of estradiol was used. This means that for every one part estrogen in the solution there are 10^48 parts water. There are only 10^80 molecules in the whole of the known universe. After a 13C dilution, there are no remaining molecules of the original substance in the produced solution. The solutions used by the study authors were many orders of magnitude more dilute than even this. In other words, study participants were given pure water.

Homeopathy is a con game. What legitimacy it might have enjoyed in 1810 has long since been abandoned. Yet the manufacturers of homeopathic products have created a huge industry around the world and homeopathic remedies can be found in virtually every pharmacy in the United States for a variety of ailments ranging from headaches to sleep aids to constipation. All of these, if they are a solution contained in water, are just pure water. Yes, people are happy to buy them, often at outrageous prices, because they either don’t understand what a homeopathic product is or they actually believe that water that once contained something in it remembers through atomic vibrations the former substance and that those atomic vibrations can cure disease. If they actually believe this, they do this without any scientific evidence that such nonsense actually happens and without any replicated high-quality studies that indicate that homeopathic treatments treat any disease or condition.

In fact, there is no legitimate scientific body that gives homeopathy even the time of day. The Federal Trade Commission recently ruled that all homeopathic products sold in the United States must contain the following warnings on their labels:

- There is no scientific evidence backing homeopathic health claims

- Homeopathic claims are based only on theories from the 1700s that are not accepted by modern medical experts

Unfortunately, Ms. Krader didn’t even have the decency to include these mild admonitions in her article which will serve as a boon to homeopathic conmen around the world. I suspect that she doesn’t know what homeopathy is even though she has enjoyed a 30+ year career in writing and reviewing medical literature for doctors. Like most patients, and I suspect most physicians, Ms. Krader likely believes that homeopathy refers to natural medicine, whatever that means. I doubt she understands that the study used pure water as treatment.

The final paper was actually published in the European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Again, I doubt that the incompetent editors or peer reviewers of that journal understand what homeopathy is either. At least I hope they do not; the worst scenario is that they do understand what it is, but believe that a poorly done study with a P-value of less than 0.05 means that the hypothesis is true. Let’s put this into perspective: by this standard, there is now as much evidence that pure water is an effective treatment for endometriosis as there is that magnesium sulfate prevents cerebral palsy in exposed newborns. Both hypotheses have the support of poorly conducted studies with poor statistical analysis.

This reinforces the absurdity of our current scientific publication crisis: it is not enough that a paper have a P-value < 0.05. We have to account for everything else we know about the subject matter and then interpret a study in the context of the pre-study probability that the hypothesis is true. What is the probability that a 24C dilution of estrogen is an effective treatment for endometriosis pain, given all that we know from the last 250 years about homeopathy and other related fields, like physics? I will never say that the probability for anything is zero; I happen to be a very open-minded person. That being said, given all that we currently know, the probability is on the order of less than one in 1 trillion. I am not being sarcastic, I am being scientific. The study should never have been published, let alone published in any mainstream journal, and it should never have been reviewed without harsh criticism in the derivative literature. Unfortunately, this is a major win for the con artists who seek to exploit people out of their money, while they forego other treatments which may actually help them. The Internet is already full of dozens of reports of the publication of this study, as if it erases 250 years of negative data related to homeopathy. Only when you view the world through the process of Bayesian updating can you understand how absurd this truly is.

Just remember that if an article like this can make it into a major publication, then anything can. All literature must be read with a critical eye and questioned. The more that nonsense like this is published, the more likely the general public will be incredulous of evidence-based medicine and the more we will see confusion like vaccine denial. Thomas Paine said,

To argue with a person who has renounced the use of reason is like administering medicine to the dead.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated example. In this week’s Ob Gyn News email blast, the lead article was entitled Dysmenorrhea and ginger. This article, written by physician (not an obstetrician), reports on a low-quality meta-analysis of low quality primary papers which suggested that ginger may be an effective treatment for dysmenorrhea. I’ve looked at these articles for you, and without wasting any more of your time, I can tell you that ginger is not an effective treatment for dysmenorrhea. My point, though, is that the publishers of both email blasts know that physicians are more likely to click on these links which contain absurd claims than they are to click on links of more legitimate science. Such click-bait is the reason why fake news exists; media outlets would not produce it if people weren’t so eager to consume it. I’ll encourage you to think about the ethics of this when such click-bait influences how physicians treat patients.

If physicians do not stop being lazy about how they learn information, we will never make progress with general scientific literacy in society and we will be perpetually handicapped in improving the health of our patients. Examples like these are unfortunately commonplace; I see them almost every week in email blasts from a variety of sources. Physicians also learn nonsense from their social media newsfeeds. This recent post has gone viral and it claims that since 2006, birth control pills have saved the lives of 200,000 women from endometrial cancer. It refers to a recently published scientific study and summarizes its contents for the reader. I have seen this claim and this post retweeted or reposted by several physicians and others who are upset about the current US President and the potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act, which might decrease access to birth control pills. When you see and believe something that makes you feel good or reinforces what you already believe, this is called confirmation bias, and you should check the source. When I first saw the claim of 200,000 lives saved, my first thought was that there must be a typo, because the number seems absurd given what I know about the epidemiology of endometrial cancer. So I pulled the original article.

Here is the original study published in The Lancet. What it actually says is that about 200,000 cases of endometrial cancer have been prevented since 2006 in the developed world; but this is not the same thing as saying that 200,000 lives have been saved. Most cases of endometrial cancer are cured with simple hysterectomy. The ten year survival rate for women with endometrial cancer is about 80%, and the 10 year survival rate for women with endometrial cancers diagnosed at an early stage is about 95%. Not all women who die in the survival period necessarily die of endometrial cancer; many would have died even without the diagnosis. So, it would be more realistic to say that perhaps 25,000 lives have been saved in the developed world in the last decade. That’s 2500 lives a year or perhaps about 800 per year in the United States. But even this number is not accurate because it assumes that no lives are lost using birth control pills; in other words, it it does not relate a total mortality improvement. About 2.2 deaths per 100,000 birth control users occur annually, mostly due to thromboembolism. In the United States, this means that about 250 women a year die because of the birth control pill. There may be other unintended consequences as well.

Note that I am not saying that using birth control pills is a bad thing. I firmly believe that they do save lives – not just from endometrial cancer but also from ovarian cancer and mortality related to unintended pregnancy. But there is a big difference between 5000 or 6000 lives saved over a 10 year period and 200,000 lives saved. This sort of myth originated in shoddy reporting and had its amplification in physicians who repeat such nonsense without checking the sources.

All sorts of “scientific publications” participate in this type of nonsense. If editors and peer-reviewers won’t take a stand then the readers must. Your patients trust you to deliver high-quality and evidence-based care to them; are you doing all that you can to do that?